Stop-Motion Animation

AFTER-SCHOOL EDUCATOR GUIDE

Stop-Motion Animation is a method of filmmaking made up of multiple photographs that change in small increments. When the photographs are played together in sequence, it is animated into . Often created with 3d objects, paper cut-outs or drawings, the magic of stop-motion is in how inanimate objects come alive through the manipulation of time, sequence, visual perception, and creative storytelling.

We love stop-motion animation because it places children’s stories, artistic expression and technical fluency all on equal grounds as they explore the best techniques to match their narrative and vision. This creates a unique opportunity to explore STEM principles in the service of the development of stories that are rooted in youth’s own lived realities, social, political and personal.

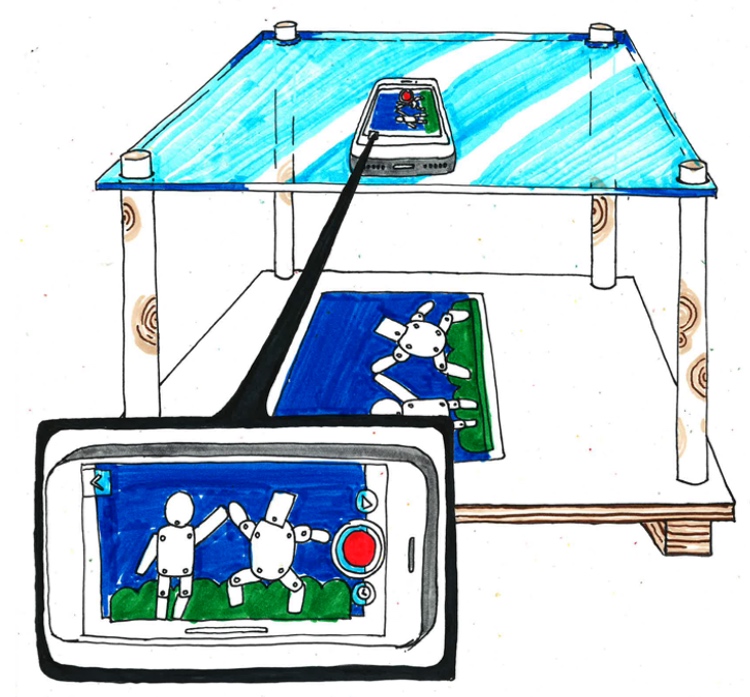

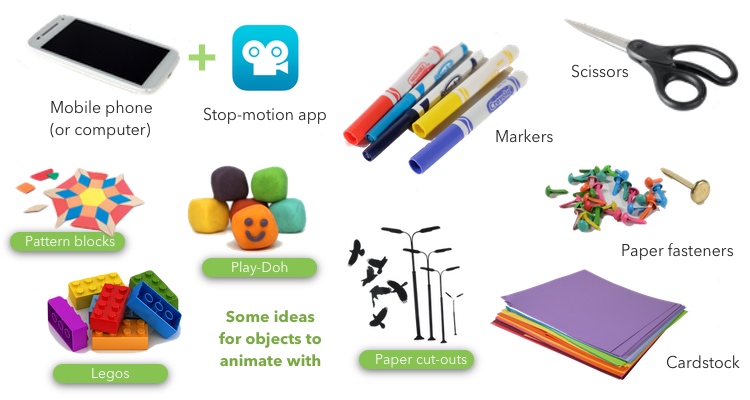

You’ll need to prepare your animation stages/rigs ahead of time. We've created instructions for these 3 different kinds of simple set-ups. Click each rig image for build instructions.

Regardless of what kind of stage you create, it is important to find some way to keep the device with the camera in a fixed position. The magic of animation is achieved by moving objects against a static background and within a still frame.

We sometimes make our characters and scenery with a craft cutter. Craft cutters are an affordable (~$150) digital fabrication tool that has the ability to cut complex shapes out of paper and vinyl. The design and computation skills learned to use it are transferable to larger-scale tools like laser cutters and CNC machines. Because so much of animation involves repetition and small increments of change, cutting multiple versions of a character in different positions seems to be a perfect job for the craft cutter. Such as the bat in flight here, a tree cut at 4 different sizes in order to show depth in a landscape, or a variety of mouths and eyebrows to animate a face. See this tutorial tracing and cutting silhouettes.

Take a photo to start and then move your pieces a tiny bit at a time, taking photos between each move. The more photos you take of one movement, the slower and smoother it will play. For fast movement, move the pieces more between each photo. You need 5 photos for just 1 second! This is called the “frame rate” and you can adjust it in the settings of the StopMotion app.

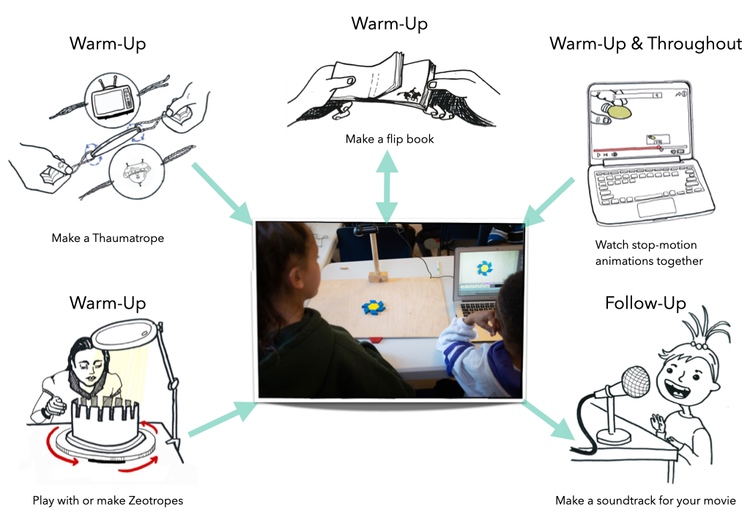

Warm-Ups & Follow-Ups

We usually like to offer youth a few low-stakes exploratory experiences with animation before getting started making a whole movie. We recommend designing experiences that help students get a sense of how movement is broken down into multiples steps - and just how many of those steps is necessary for fluid movement. Help kids orient themselves to telling stories that happen in short scenes that are not too long considering the limitations of animation. Below are a few of our favorite opening activities and scaffolding projects:

Watch Thaumatrope Video Watch Zoetropes Video

Collaborating is hard work

Sharing equipment offers a great opportunity for collaborative work. It also puts a demand on students to figure out how to collaborate. Sometimes the division of labor that young people settle into works well. However, separate roles can also replicate common inequities. Keep an eye on groups and intervene when necessary with suggestions for new structures of collaboration. For example, ‘how about you each have a character and improvise a story together?’

Sharing equipment offers a great opportunity for collaborative work. It also puts a demand on students to figure out how to collaborate. Sometimes the division of labor that young people settle into works well. However, separate roles can also replicate common inequities. Keep an eye on groups and intervene when necessary with suggestions for new structures of collaboration. For example, ‘how about you each have a character and improvise a story together?’

Movies are too short!

Sometimes students rush the process by taking only a few photos for each movement, or they may enjoy their story so much that they forget to take photos as they go. This results in choppy movies that don’t do justice to their ideas. Encourage students to play their movies often and evaluate how it looks. You could offer to be the picture-taker for a turn to model a workflow of taking lots of photos while the student creates the story. Teams of students often develop gestural or verbal cues so that they know when to remove hands to take a photo. You can also model this so that kids develop a rhythm for taking lots of frames of small movements.

Sometimes students rush the process by taking only a few photos for each movement, or they may enjoy their story so much that they forget to take photos as they go. This results in choppy movies that don’t do justice to their ideas. Encourage students to play their movies often and evaluate how it looks. You could offer to be the picture-taker for a turn to model a workflow of taking lots of photos while the student creates the story. Teams of students often develop gestural or verbal cues so that they know when to remove hands to take a photo. You can also model this so that kids develop a rhythm for taking lots of frames of small movements.

Lots of text, little movement

Often kids want to include dialogue in their stories but including text can present lots of challenges. The text needs to be on the screen long enough for the viewer to read it, for example. We’ve noticed that often when kids start using text, they spend less time on animating motion and other visual effects. For this reason, we often discourage text dialogue and instead show how characters can express emotion and intention through gesture and movement. Students might also record an audio track if the dialogue is really important to them.

Often kids want to include dialogue in their stories but including text can present lots of challenges. The text needs to be on the screen long enough for the viewer to read it, for example. We’ve noticed that often when kids start using text, they spend less time on animating motion and other visual effects. For this reason, we often discourage text dialogue and instead show how characters can express emotion and intention through gesture and movement. Students might also record an audio track if the dialogue is really important to them.

Kids are making really violent stories!

Any time we prompt kids to tell stories, we are opening up a space for any kind of story! Some of them are lighthearted but some stories may be serious or violent. This is such a common occurrence with animation that it is helpful to discuss strategies with your team before starting. It’s worth acknowledging that adult-produced movies, tv, and news media are full of darkness so it makes sense that kids explore their ideas through similar stories. Violence can also be a powerful part of how storytelling can help kids make sense of violence they may have seen, felt or experienced in their own lives. If educators make violence off-limits, it could close this unique opportunity.

Students are moving the cameras

When young people move the cameras or pick up the tablets being used for stop-motion, they could be exploring a number of ideas. If it was unintentional, they can use the “onion skinning” feature of the app to reposition the camera and keep working. Sometimes students move the camera to explore special effects or to include themselves in their movie. Like gently shaking a camera to create an earthquake effect. Carefully consider what’s being explored before offering advice; rule breaking is often part of the process of expanding technical creativity and expression.

This guide was co-authored by a group of after-school educators and university professors of education working in 3 different after-school centers. Here, some of the after-school educators share their big picture ideas behind their choices and experiences while designing this activity for their programs.

Jake Montano, Exploratorium:

Jake Montano, Exploratorium:

“Sometimes when beginning stop motion projects, kids can get stuck trying to figure out where to start. I used the vinyl cutter to assemble eyes, eyebrows, lips, shoes, arms, and more to give them a place to start. It was important to me that kids could see themselves in the images and phenotypes as they animated facial expressions, songs or dialogue. I also cut out blue arms and race-cars to give them space to make things that were completely other than human forms. I found that offering a mix of structures helped kids get started but also allowed a lot of freedom to create whatever they wanted from their imagination.”

Aurora, Watsonville Environmental Science Workshop:

Aurora, Watsonville Environmental Science Workshop:

“Stop motion allowed me to get to know kids on a deeper level. Often you don’t know what kinds of problems kids have in their lives and they may not trust adults. Using stop motion helped me understand more about kids’ lives and stories who may not otherwise share.”

Darren Gertler, Watsonville Environmental Science Workshop:

“At the Watsonville Environmental Science Workshop, many very young students (ages 5-8) come to the workshop during drop-in hours. A group of younger students gravitated towards a recently donated box of play-doh one afternoon. They were very adept and familiar with Play-Doh and it became their medium of choice for Stop Motion Animation. After a few minutes, they turned their stop-motion stage on its side so that they could animate in 3 dimensions. This student-driven alternatives seemed more familiar to them and reflected the TV shows and media that they know.”

“At the Watsonville Environmental Science Workshop, many very young students (ages 5-8) come to the workshop during drop-in hours. A group of younger students gravitated towards a recently donated box of play-doh one afternoon. They were very adept and familiar with Play-Doh and it became their medium of choice for Stop Motion Animation. After a few minutes, they turned their stop-motion stage on its side so that they could animate in 3 dimensions. This student-driven alternatives seemed more familiar to them and reflected the TV shows and media that they know.”

Cultural and Historical Origins

Often, when we learn about the origins of animation, images from the Victorian age of Western Europe seem to be the most available. These Victorian zoetropes-like toys also reflect the values of that time- one of the most common images are of a bird in a cage. However, images depicting animated movement have been traced back over 5,000 years. For example, this jumping desert Ibex (a wild goat indigenous to the area it was found) is painted onto an earthenware bowl made in what is now known as the Burnt City of Iran. The bowl itself would function as a zoetrope when spun and viewed through a narrow slit like the space between your fingers. We like to offer youth alternative histories like this one as a way to expand our definitions of what counts as technology and who gets credit for inventing and using it.

Powerful Ways to Support Learning

Stop-motion animation provides powerful ways to support children’s thinking, problem solving, and imagination. As the early childhood teacher and researcher Vivian Paley explains, children love to explore the themes of “the three Fs” -- fantasy, fairness, and friendship. When given the opportunity to write, play, and dramatize around these themes, children’s engagement soars and their ability to think through challenges increases immensely. Here is a link to her complete article.

Children’s stories also allow them to explore injustice and/or violence in their lives. The authors Emily C. Price and A. Susan Jurow suggest that “when we do not provide children space to discuss what they are experiencing or seeing, they are deprived of the opportunity to process their experience” and make sense of their worlds (p. 18). Stop-motion animation provides rich ground to help young people explore challenging social and political material that, like adults, they also need supported spaces for processing. Here is a link to their complete article.

Stop-motion animation projects often involve coordination between people, tools, and ideas. How we decide to organize this work shapes what people learn and how. The researchers Jacquelyn Baker-Sennett, Eugene Matusov, and Barbara Rogoff found, in their study of 1st/2nd grade students, emphasize that children benefit from getting to plan their own dramas. They get to figure out what characters, what storylines, and what scenes need to come together to tell a compelling story. This article reminds us that there is learning taking place as young people plan storylines together with adults as interested listeners. Here is a link to their complete article.

HOW IS IT High Tech Low Cost?

We use the term High Tech Low Cost for projects that use “high-tech, low-cost” digital tools while engaging in high-complexity thinking and creating. We believe that cost shouldn’t be a barrier for meaningfully including technology in creative learning. We find that stop-motion animation is a very low-barrier entry for youth to create with both digital platforms and physical objects simultaneously. It can be done with participants or facilitator’s own smartphones, tablets or computers using free animation applications. The frames can also be edited manually in more complex video editing software if students want to take the editing further.

Thanks to the generous funding of the National Science Foundation.